Information for Health Care

Providers

Distinguishing Between

Influenza-like Illness

and Early Inhalation Anthrax

In most circumstances, the

Illinois Department of Public Health does not make specific recommendations

about patient care. However, it is providing the following information, which

may help with clinical decisions. Ultimately, though, clinical decisions about

patient care remain with the health care provider.

It is important that health

care providers follow reporting requirements. When a diagnosis of a

bioterrorism-associated illness is suspected, it is critical that the case be

reported to the local health department within three hours of such

recognition.

1. Health care providers

should review the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (November 2,

2001).

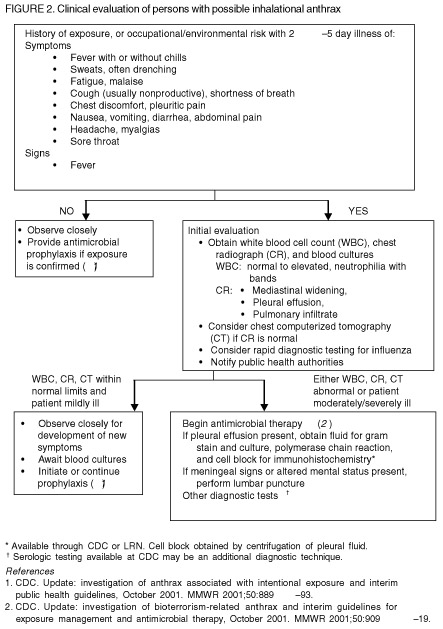

Of particular importance is

the flow diagram on page 945 (Figure 2, reproduced below). Additional guidance

from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) can be found in

the November 9, 200, issue (Vol. 50, No. 44) of the MMWR. Another article of

interest will appear in the November 29, 2001, issue of the New England

Journal of Medicine: “Recognition and management of anthrax - an

update” by M.N. Swartz.

2. Anthrax is rare and

influenza-like illnesses are common.

Although the symptoms of

influenza and influenza-like illnesses may overlap with the early presentation

of inhalation anthrax, it should be emphasized that influenza is primarily an

upper respiratory tract infection (e.g., cough and sore throat) with

accompanying fever, headache, myalgia and malaise but with a wide spectrum of

severity. Recently reported cases of inhalation anthrax , a lower respiratory

tract infection, may have minimal or nonproductive cough but frequently have

chest discomfort or pleuritic pain. When influenza is complicated by lower

respiratory tract findings, such as pneumonia, then differentiating from

anthrax may be more difficult. Whenever inhalation (or any form of) anthrax is

being considered, consultation with an infectious disease physician is

recommended.

Based on review of the

relatively few published cases of inhalation anthrax and the recent

bioterrorism-related cases, rhinitis is rarely, if ever, seen with anthrax. Its

presence, therefore, is a possible clue that influenza or influenza-like

illness is present; however, its absence is of no value because many cases of

influenza and influenza-like illnesses will not have rhinitis.

Symptoms such as fever,

sweats, chills, myalgias, fatigue, malaise, dry cough, headache and sore throat

may occur in either illness, so their presence or absence is of no value. But

the rarity of anthrax and the relative frequency of influenza and

influenza-like illnesses should be considered when doing a diagnostic

evaluation, just as the incidence of illnesses guides other decisions in

clinical medicine. Clinicians should avoid letting fear obscure sound clinical

judgment.

There are no early laboratory

clues that can be considered diagnostic. It has been noted that none of the

inhalation anthrax cases had a low white blood cell count. This information

cannot be reliably used to differentiate anthrax from other illnesses since it

is possible that anthrax could infect someone who already has a low white blood

cell count (e.g., an immunocompromised person). Also, the number of studied

anthrax cases is still relatively small, so generalizations about the disease

are limited.

3. Occupation and exposure

history should be obtained to help assess the relative risk of anthrax in an

individual presenting with influenza-like illness.

To date, nearly all cases of

inhalation anthrax have been either a postal worker, a mail handler or sorter,

or a recipient of an envelope containing anthrax spores. For a few additional

cases, the exposure has not been determined but those investigations are

ongoing. Therefore, risk is certainly increased if someone is linked to one of

the confirmed anthrax events in the District of Columbia, Florida, New Jersey

or New York City. And, heightened concern is reasonable if dealing with persons

who handle mail or who have been exposed through an incident that appears to be

credible or that was determined by law enforcement to be credible and for which

laboratory evidence has not ruled out anthrax.

4. Rapid influenza tests may

be performed to help evaluate a case of anthrax versus influenza.

Such testing has limitations

that do not make it reliable for this purpose. While makers of the rapid

influenza tests report overall sensitivity of 70 percent and specificity of 90

percent, these are likely overestimates based on unpublished data of which the

CDC is aware. In fact, it is not unusual for rapid influenza tests to yield

false positives and false negatives. During peak flu season, only one-third of

influenza-like illnesses submitted for viral testing actually test positive for

influenza. The positive predictive value of these tests suffer during non-peak

portions of the flu season. So, a negative rapid influenza test does not mean a

person has anthrax.

5. To date, there have been no

cases of anthrax nor environmental test results positive for anthrax in

Illinois.

Millions of cases of

influenza-like illness occur every year. Therefore, while public health

officials and health care providers need to be in a state of heightened

awareness for anthrax, it is important to keep in mind that, for any individual

case, the odds are very small that it is truly anthrax.

6. If diagnostics are

performed to evaluate a possible human case of anthrax, such specimens should

be initially processed in a local hospital or other qualified laboratory,

unless such testing requires specialty techniques such as PCR or

immunohistochemical testing of tissue.

If test results suggest the

presence of a Bacillus species that may be B. anthracis, then the

local health department should be notified immediately so that staff can

consult with IDPH laboratory personnel or the Department’s infectious

disease staff about forwarding such specimens to the state laboratory for

confirmation or speciation.

|